Vagabond Journey.com History of the Tibetan Nomads Home

Travelogue

Travel Blog

Directory

Travel Photos Travel Tips

Travel Questions Forum

Travel Guide

Map of the Tibetan Autonomous Zone.

| Wade from www.VagabondJourney.com has been continuously traveling around the world He is open to answer all questions - email Vagabondsong@gmail.com. Walk Slow. |

| Thesis Table of Contents: Part I- Introduction Part II- History of Arunachal Pradesh Tribals Part III- History of Tibetan Nomads Part IV- Early Development of Arunachal Pradesh Tribals Part V- Recent Developments in Arunachal Pradesh Part VI- Early Development of Tibetan Nomads Part VII- Recent Developments in Tibet Part VIII- Conclusion Part IX- Bibliography |

History of the Tibetan Nomads

Not wanting to enter the tent, I looked up at the sky. Brilliant sunlight shown from above. I could see far into the distance and I enjoyed it.”-Karma-Dondrub

“On the grazing lands of Tibet you live

in the present.”

-Rangeland Ecologist, Daniel Miller

“The whole life of the nomads is

organized so as to make the most of the scanty aids to living which

nature provides. At night they sleep on skins spread upon the ground

and, slipping out of the sleeves, use their sheepskin cloaks as

bedclothes. Before they get up in the morning, they blow up the still

live embers of their fire with a bellows and the first thing they do is

make tea.”

-Heinrich Harrer, Seven Years in Tibet

“Men in sheepskin clothing and with

long braided hair trotted past on stout ponies. Sitting on high-backed

saddles on top of colorful saddle carpets, with rifles slung over their

shoulders and long swords dangling from their waists, these horsemen had

a haughty air of confidence about them.”

-Heinrich Harrer, Seven Years in Tibet

Since time unmemorable the nomads of the Tibetan plateau have lived in accordance with the ancient ways of the pastoralist. Forever in tune with the tidings of their environment, deities, and herds, they travel yearly circuits up to the high Himalayan altiplano and then back down to the fertile mountain valleys. With lives and economies completely divested in their herd animals and hearts fully devoted to their beloved Buddha Dharma, the Tibetan nomads continue to mark out an existence that has long been wrought from most of the world.

-------------------------------

Written and researched by Wade Shepard of

www.VagabondJourney.com

Senior Thesis, Friends World Program, Long Island University

Travelogue --

Travel Photos --

Travel Guide

Thesis Contents:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

---------------------------------

Please be aware that I am not intend upon producing a complete document on Tibet

Neither nomadism, nor do I balk at the fantasy that this is even a possibility. The externally mandated time and spatial demands of this section of this thesis decree that I err towards brevity and conciseness. I simply want to provide the reader with a general introduction to a way of life that the Tibetan Nomads (here referred to as a single ethnic group) lived prior to the forced introduction of Chinese policy, economic schemes, and social dispersal. My sole aim in writing this background is to make an attempt at shedding light upon the old ways of the Tibetan pastoral nomad. Please also note that I do not even make mention of semi-nomadism, and the criteria by which we, who are external to Tibet, delineate nomads (as migrants) are much different than those of Tibetans; who consider a nomad as someone who, simply, derives their livelihood and resources from animal husbandry.

The region that is now known as historic Tibet encompasses the entire distance from central Sichuan province (103- 104 degrees East longitude) in the east to the Pakistani and

Indian borders in the west, from mid Yunnan province (east) and the Nepal border in the south to the frontiers of Xinjiang and Gansu provinces in the north. “When the PRC [People's Republic of China] refers to Tibet, it means the TAR [Tibetan Autonomous Region]. When the Dalai Lama speaks of Tibet, he refers to the broader area in which ethnic Tibetans reside, including the TAR as well as the high plateaus of Qinghai, Gansu, western Sichuam, and northernmost Yunnan provinces.”1 This entire area was once divided between the Tibetan kingdoms of Amdo (modern Qinghai), Kham (Yunnan, Sichuan), Chang Thang (within Tibet Autonomous Region [TAR]), Ngari (western boundary of TAR), Nagchuka (eastern TAR), and Tsaidam (located in extreme north of historic Tibet). The total area that these kingdoms encompassed was over 2.5 million square kilometers; which is roughly the size of Western Europe.

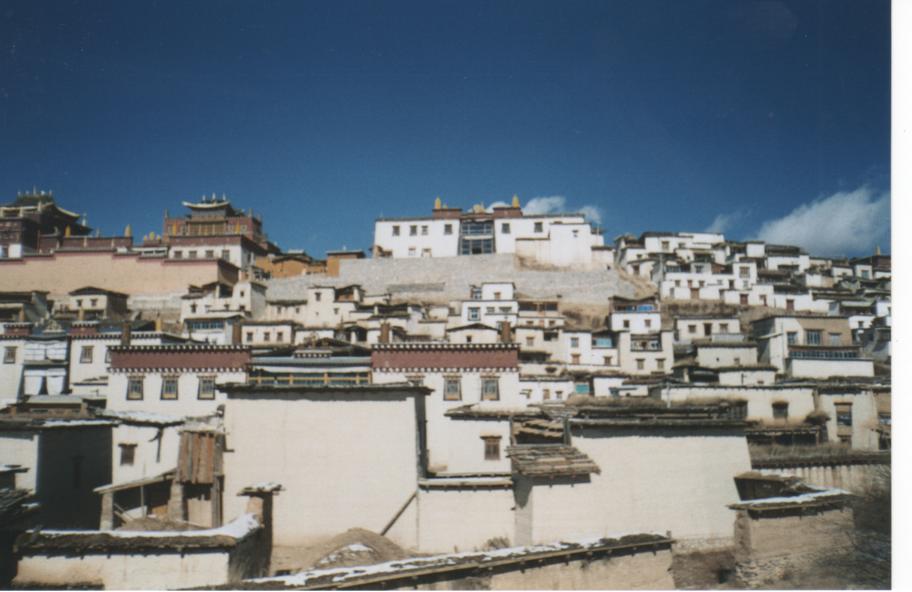

Pagoda in the mountains of the old Tibetan kingdom of Kham, which is not modern Yunnan Province of China.

Geographically speaking, Tibet is an incredibly mountainous region, with the

Himalayas, the world’s highest mountain range, and its associated highland making up its entire southern and eastern portions. Nearly everywhere in the region is at an altitude above 3,000

meters, with many inhabited locales measuring up at far over the 5,000 meter mark. The northern areas of the Tibetan region are vastly sprawling grasslands which are utilized by nomads as grazing ranges. This portion occupies approximately half of the Tibetan land mass. The eastern quarter of Tibet consists of dense forests which, “run the entire breadth and length,” of the area.2 The southern portion is somewhat agriculturally dominated and includes the main centers of Tibetan civilization: Lhasa, Shigatse, Gyantse, and Tsetang.3

The climate of the Tibetan region can be generalized as being harsh, arid, temperamental, bright, dry, and, through the long winters, frigid. As the rangeland ecologist, Daniel Miller, puts it, “Even in the height of summer, snow and hail storms are common and when they come blowing down out of the mountains you better have your act together. There is little room for error.”4 But, even though it is very cold, precipitation over most of the Tibetan region is scarce, which results in the extreme aridity of much of the plains areas. This also has the effect of causing the atmosphere to often be devoid of clouds, which allows the sun to pour through to the land unimpeded. Tibet is one of the brightest regions on the planet, logging nearly 3,000 sunshine hours a year.5 In winter, the temperatures of many areas can plummet to far below negative 16 degrees centigrade. A testament to this extreme cold was made by Heinrich Harrer, “. . . my thermometer showed an unvarying temperature of -30 degrees Centigrade. There were no lower markings on the instrument.”6 Owing also to the thin highland atmosphere, there is little to absorb the heat and rays of the sun, which results in harsh daytime ultraviolet light exposure followed up by frigid nights. In such a parched, temperamental region, the communities that live here needed to adapt ingenious mechanisms, practices, and community initiatives just to survive.

The culture of the Tibetan Nomads primarily revolves around the practices of herding, trading, religious devotion, and, encompassing all three, migration. The ways and practices of the nomads are ancient and have been shaped through the necessities created by the harsh mountain ecosystem that is their home. The impact that environmentally mandated necessity has on Tibetan culture can not be under-estimated, and the impact of which occasionally results in a manner of cultural amorphism- where the ideal social dichotomy is mandated by what is environmentally possible.7

The nomadic Tibetan family structure is one such social institution that lends credentials to the above statement. Nomadic Tibetan dwellings (generally tents) usually contain a single family unit which often times includes grandparents. When a couple is married it becomes a community decision as to which family (either bride’s or groom’s) they should live with or if they should begin their own household. This is occasionally a matter of contest, as issues of family pride, history, and practical circumstance are taken into account. An example of this is drawn out by Karma-Dondrub in his autobiographic account of his upbringing in Tibetan Nomad Childhood:8

Metog’s parents said that Ringchen should come to live with them. Tsormo (Ringchen’s mother) said that she would never Ringchen live under other’s control. She added that it was better if Metog (Ringchen’s bride) came to lived with us. I asked Ringchen his idea. He said he wanted to live with his parents. But I couldn’t agree, since our daughter-in-law comes from a family seriously affected by leprosy. I was afraid of ruining our claim to clean bones if she came to live with us. What I wanted was for the new couple to set up their own family.

The harshness of environmental and social conditions also leads to many family arrangements that can only be described as happenstancial. Polygamy and polyandry all have places within the Tibetan Nomad’s living strategy. During his journey through Tibet, Heinrich Harrer noted various domestic situations with puzzlement:9

She told us that her two husbands had gone out to drive in the animals. . . We were astonished to find polyandry practiced among the nomads. It was only when we were in Lhasa that we came to know all the complicated reasons that led to the simultaneous existence in Tibet of polyandry and polygamy.

The social structure of most nomad communities are arranged hierarchically, with a sole leader and set chain of command. But although there is a single leader this is in no way a dictatorial system, as consensus and majority rule are often employed within the decision making process. In most cases, all major decisions are made during community meetings in which everyone is allowed to speak freely and decisions are usually made subsequent to open debate. It is also a regular occurrence for multiple community units to join together into federations that are lead by a single, collectively elected leader.10 I stress that there are many different situational variations in the organization of nomad communities, I can only present a rough syntheses base upon my personal research and observations.

In an overall sense, Tibet society is traditionally highly stratified, and is in the customary triangular shape of the conventional hierarchy: a few people at the top and many at the bottom. Prior to the Chinese restructuring of Tibetan society, there were three distinct social classes: the monks, the nobility, and the ordinary lay people, who could be considered peasant farmers, nomads, or pastoralists.11

The Tibetan Nomads lives and works in accordance with ebb and flow of the seasons. In summer it is time to lead the herds up to the high alpine pastures, trade with townsfolk, and prepare for the harsh season to come. In winter, the Tibetan Nomads move down into camps that are at a lower, warmer, altitude. In recent times, solid brick houses have been constructed to make the cold season a little more bearable. The winter season is one of rest as there is not as much work to be done and, due to the extreme cold, activity is lessened to the bare essentials. As Heinrich Harrer puts it:12

In winter the men living a nomad life have not much to do. . . The women collect yak dung and often carry their babies around with them as they work. . . As one can imagine, the nomads have the simplest methods of cooking. In winter they eat almost exclusively meat with as much fat as possible. They also eat different kinds of soup- tsampa, the staple diet in agricultural districts, is a rarity here.

Religious devotion is a central, essential, part of Tibetan life. Their belief follows that of the Buddha Dharma with intensely strong traditional undercurrents. Buddhism was first introduced into Tibet in the early seventh century but did not take hold across the entire culture until the ninth or tenth century.13 The Indian (and perhaps Chinese) Mahayana, Hinayana, yogic, and Tantra traditions that were introduced into Tibet were greatly synthesized and assimilated into the pre-existing spiritual tradition and the result, Tibetan Buddhism, arose as something new and pure. Tibetan Buddhist is centered upon sutra recitation, meditation, and Tantra:14

Tantric systems transform the basic human passions of desire and aversion for the purpose of spiritual development. Rather than denying such primal urges, tantra purifies them into wholesome and helpful forces.

Tibetan Buddhism has, ultimately, became the religion of Tibetans across the entire plateau and has grown and expanded into multiple sects and subgroups.

The life of the Tibetan Buddhist is, ideally, one of continuous devotion, compassion, ceremony, and role. Prior to the 1949 Chinese invasion, almost every family had at least one son in the monastic system and would provide a hefty portion of their family resources to the monastery. In turn, the Llamas and monks would perform the necessary life rituals- marriage, death-rites, births, divination, and other ceremonies in which a sage’s good wishes would be auspicious. The Nomad populace is, almost all-inclusively, highly devoted to the tenants of Tibetan Buddhism:15

. . . one finds an alter in every tent, which usually consists of a simple chest on which is set an amulet or a small statue of the Buddha. There is invariably a picture of the Dalai Lama. A little butter lamp burns on the alter, and in winter the flame is almost invisible owing to the cold and the lack of oxygen.

The Tibetan moral system is based around the accumulation of merit and the prospects found in reincarnation. Merit can be roughly explained within the frame of idealized karma and reincarnation; in which deeds and actions that are considered “good” are rewarded with the potential of a higher re-birth and deeds that are thought to be “bad” add up to a lower reincarnation. “Taking of life, whether human or animal, is contrary to the tenets of Buddhism, and consequently, hunting is forbidden.”16 The fact that the Tibetan diet is meat dominant presents no contradiction; as the accumulation of bad merit falls upon the ones committing the deeds rather than whom they are doing it for (this is another example in which Tibetan culture adapts with what is environmentally dictated, as the Tibetan climate demands the consumption of animal products).

The worship of nature deities continues to occupy a powerful place in Tibetan spiritual practice. Traditionally, Tibetans use mountains and their specific deities as a way of conceiving their place in the world and cosmos. Every clan has a local mountain that is tied to their community and it assists in allowing them to, metaphysically, weave themselves into the landscape and heaven.17

The worship of mountain gods and other local deities is not just a minor domain of Tibetan religion but a more general political and cultural phenomenon. The mountain cult is an essential element in Tibetan culture and is part of collective identities which are expressed in the form of specific local economic and political behavior.

The religion and spirituality of the Tibetan Nomads provides the cord by which the major aspects of their culture, landscape, and climate are tied together. In times of celebration as well as tribulation Buddha and the Mountains are invited to accompany and console the people by whom they are deified.

The economy of the Tibetan nomads is focused around pastoralism and, by extension, the transactions that are derived from such. The lifeblood of the Tibetan nomad’s way of life is derived from their pack and herd animals; which require continuous adherence to seasonal migration routes:18

Mobility is a characteristic of Tibetan nomadic production systems. Herds are regularly moved between different pastures to maintain range land productivity. Tents, such as yak hair tents, enable Tibetans to move easily. Without the yak it is doubtful if people could survive in Tibet. In addition to providing hair for tents, yaks also provide wool for clothing, bags and ropes. They are milked and milk is made into butter and cheese. Their dung is used for fuel wood in a land where trees can not grow. Yaks also carry supplies and are used for riding.

Much of the Nomad’s sustenance comes directly from their animals. Their food largely consists of sheep, yak, and goat meat, tsamba, and various dairy products. The Nomad’s produce their clothing from the hides and wool of their sheep and yaks. Horses and yaks also serve as the predominant sources of transportation; as the Nomad communities are nearly completely devoid of any vehicles.

Most Nomad communities engage in at least some form of trade with other Nomads and villagers. Certain agricultural and, contemporarily, industrial commodities are needed by the Tibetan Nomads, which necessitates bartering with outsiders who have access to these resources. Often, Nomads take selected animals into village markets to sell and then purchase various agriculturally derived produce to take back to their communities. By current standards, a high quality yak will sell at market for 2,500 Yuan.19

The Tibetan nomads generally travel along arranged paths to particular pasture lands that correspond in altitude with the season. In the summer, they usually travel up into the mountain highlands so that their animals can feed upon the fallow growth. In the winter, the nomads usually move down into the valley pastures and wait out the season. In this way, the nomads of Tibet live a very natural life; forever moving with the cycle of nature, rather than in opposition to it. This feeling of effervescent unity is explained by Miller:20

Here is a landscape full of energy. You quickly become charged. There is simple enjoyment in getting back to the basics. You know when the sun comes up. You watch every sunset. You know the phases of the moon. You’re on moon time out there.

Under the traditional system (prior to the 1949 Chinese invasion) the nomads grazed their herds on large land masses that were the property of a particular religious leader, who would act in capacity very similar to that of an overlord of a fiefdom. “Like peasants on agricultural estates, these nomads were hereditarily tied to their estates and did not have the right to take their herds and move to the estate of another lord.”21 But although they did not own the land that they grazed their herds upon, they did own the animals themselves, as well as all of their personal property. They were obliged to pay taxes to the estate owners; which consisted of pre-arranged amounts of their animal’s produce. In exchange for this, the property owners allowed the nomads free range of access upon the land. The owners also did not engage in the practice of evicting pastoralist from the grazing land that was, essentially, their home.22

Thesis Contents:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Footnotes:

1Debra E. Soled, editor. China: A Nation in Transition (Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly Inc., 1995). 303.

2Asia Planet, Tibet Information, http://www.asia-planet.net/tibet/information.html.

3Ibid.

4 4Daniel Miller, A Journey Through the Nomad Camps, http://surfart.com/Tibet-Online/ Nomads/nomadcmp2.htm.

5Anonymous, Tibet Information, http://www.asia-planet.net/tibet/information.htm.

6Heinrich Harrer, Seven Years in Tibet (New York: E. P. Dutton and Co., Inc., 1953) 38.

7This idea is my own and is based off the readings of a conglomeration of first person accounts rather than one solid source...ex. Harrer, Neal, Rock.

8Karma-Dondrub, Tibetan Nomad Childhood, (Copyright: Karma-Dondrub, 2005), 107.

9Heinrich Harrer, Seven Years in Tibet, (New York: Penguin-Putnam Inc., 1953), 95.

10Information taken from the three stories written by Gongboo Sayrung, Guhruh, and Karma Dondrub in the book, Tibetan Childhoods and Tribal Heroes.

11Childs, Geoff. 2003. "Polyandry and population growth in a Historical Tibetan Society", History of the Family, 8:423–444.

12Ibid. 88.

13John Vincent Bellezza, Nothern Tibet Exploration, http://www.asianart.com/articles/tibarcheo/index.html.

14Anonymous, Tibetan Buddhism, http://homepages.ihug.co.nz/~greg.c/tibet.html.

15Heinrich Harrer, Seven Years in Tibet (New York: E. P. Dutton and Co., Inc., 1953), 96.

16Heinrich Harrer, Seven Years in Tibet (New York: E. P. Dutton and Co., Inc., 1953), 40.

17Anonymous, Tradition and Modernity in Tibet and the Himalayas, http://www.oeaw.ac.at/sozant/tibet/projects/mountdeities.htm.

18Daniel Miller, A Journey Through the Nomad Camps, http://surfart.com/Tibet-Online/ Nomads/nomadcmp2.htm.

19Karma Dondrub, Tibetan Nomad Childhood, 47.

20Daniel Miller, A Journey Through the Nomad Camps, http://surfart.com/Tibet-Online/ Nomads/nomadcmp2.htm.

21Melvyn C. Goldstein; Cynthia M. Beall, “The Impact of China’s Reform Policy on the Nomads of Western Tibet,” Asian Survey, University of California Press, (1989): 621.

22Ibid. 623.